Greek War of Independence

On March 25, Greece celebrates Greek Independence Day, a national holiday honoring the date when the War of Greek Independence first began in 1821. It corresponds with the Greek Orthodox Church’s celebration of the Annunciation to the Theotokos, when the Archangel Gabriel appeared to Mary and told her that she would bear the son of God.

The Ottoman Empire had included Greece since 1453. When Bishop Germanos of Patras hoisted the revolution banner over the Monastery of Agia Lavra in the Peloponnese on March 25, 1821, it ignited the Greek uprising. The revolution’s catchphrase was “Freedom or death.” Infighting followed the Greeks’ early victories on the battlefield, which included the conquest of Athens in June 1822. The Ottomans had already retaken Athens and the majority of the Greek islands by 1827.

Britain, France, and Russia entered the battle just when the revolution appeared to be about to collapse. Strong sympathy for the Greek fight existed throughout Europe, and many notable thinkers, notably the English poet Lord Byron, supported the Greek cause. An Ottoman-Egyptian fleet was annihilated at the naval Battle of Navarino by a coalition of British, French, and Russian forces. After the Treaty of Edirne established an independent Greek state, the revolution came to an end.

Schools around Greece participate in a school flag parade when students march while wearing traditional Greek attire and carrying Greek flags in honor of Greek Independence Day. In Athens, there is also an army parade.

Learn more about the historical facts here.

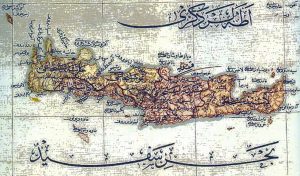

The Cretan Independence War

Although there was significant Cretan involvement in the revolt, Egyptian interference prevented it from liberating the country from Ottoman domination. Daskalogiannis, a folk hero who died while battling the Turks, is an example of Crete’s long history of defying Turkish domination. The Ottoman authorities brutally suppressed a Christian insurrection in 1821 and executed numerous bishops who were seen as the leaders.

The uprising persisted despite the Turkish response, forcing Sultan Mahmud II (reigned 1808–1839) to enlist the help of Muhammad Ali of Egypt, whom he tried to seduce with the pashalik of Crete. Hasan Pasha, Mehmet Ali’s son-in-law, led an Egyptian fleet of 30 warships and 84 transports that arrived at Souda Bay on May 28. He was tasked with putting an end to the uprising and wasted no time in starting the burning of communities across Crete.

Hussein Bey, another son-in-law of Muhammad Ali of Egypt, led a well-equipped, well-organized joint Turkish-Egyptian force of 12,000 troops with the assistance of artillery and cavalry after Hasan’s unintentional death in February 1823. The Convention of Arcoudaina was conducted on June 22, 1823, by Emmanouil Tombazis, the Greek revolutionary government’s Commissioner of Crete, in an effort to bring the factions of the local captains together and unite them against the common menace. The Cretans were defeated by the much bigger and better organized force at the battle of Amourgelles on August 20, 1823, and lost 300 men. He then assembled 3,000 soldiers in Gergeri to fight Hussein. Hussein had succeeded in reducing the Cretan resistance to a few mountain pockets by the spring of 1824.

The Cretan insurgency was revived (the so-called “Gramvousa period”) when a group of three to four hundred Cretans who had fought alongside other Greeks in the Peloponnese landed in Crete in the summer of 1825. These parties of Cretans, led by Dimitrios Kallergis and Emmanouil Antoniadis, took control of the fort at Gramvousa on August 9, 1825, while other rebels took control of the fort at Kissamos. They then tried to extend their rebellion farther afield.

The Ottomans were unsuccessful in retaking the forts, but they were successful in preventing the uprising from spreading to the western parts of the island. For more than two years, the insurgents in Gramvousa were under siege, and they turned to piracy as a means of survival. Gramvousa developed as a hub of piratical activity that had a significant impact on Turkish-Egyptian and European shipping in the area. The people of Gramvousa organized themselves during that time and constructed a school and a church honoring Saint. Mary, the patron saint of the klephts, was called Panagia I Kleftrina (“Our Lady the Piratess”).

The Epirote Hatzimichalis Dalianis arrived in Crete in January 1828 with 700 soldiers, and in March of that year they took control of the stronghold Frangokastello in the Sfakia district. Soon after, Mustafa Naili Pasha, the local Ottoman governor, attacked Frangokastello with an army of 8,000 soldiers. After a seven-day siege, the castle’s defense crumbled, and Dalianis and 385 other soldiers died. In order to deal with the klephts and the pirates, Kapodistrias dispatched Mavrocordatos to Crete in 1828 along with British and French fleets. All of the pirate ships at Gramvousa were sunk as a result of this expedition, and the fort was placed under British control.

A great parade is being held every year at 25/5 for this National Day.

In conclusion, take some time and watch the following video to get a better understanding of the importance of our National Day. Gratitude and pride fills our souls for our ancestors not so long ago, for their brave actions and sacrifice.

Book your vehicle and drive around the villages that held their ground during these times.